What if emotional trauma was transferred intergenerationally by physical scarring?

Imagine: a parent is traumatised in some way, be it through war, domestic violence, racial persecution, etc. This trauma, rather than having an intergenerational trickle effect (where the fear/anger/isolation of the parent is transferred in some diluted form to the child) it would only manifest as scar tissue on the body of the child with no emotional residue (which I imagine would feel, if rubbed between your fingers, like resin. In my mind, fear is sticky.)

This recalls, in some sense, that article I wrote about a while ago, which explored the phenomenon of descendants of Auschwitz survivors having the survivors’ tattoos inked on their own skin. Although this is voluntary on the part of the descendant as a testament to the survival of their relative, it echoes this idea of a physical manifestation of past experience. Imagine if this was a way that we could read a person’s history.

We could literally read it on their body. Like in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, where the main character’s back is covered with a cherry blossom tree (which you come to realise is the latticework of scar s left from when she was a slave), we could read struggle, and past struggle, on skin. I could take your hand, or left shoulder, or elbow-bend and run my fingers over the lines of thick dense tissue and ask you what’s happened to your family.

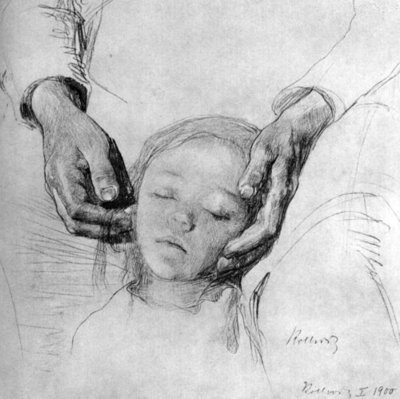

This sketch is by Kathe Kollwitz and is called Kopf eines Kindes in den Händen der Mutter or Head of a child in the hands of the mother. It was this that set my braining running on this question. Imagine if we could suspend the pain of survival and replace it with scar tissue. But wouldn’t we want to feel the pain of the struggle that it took for our parents and our grandparents to survive? Otherwise we’d risk slipping back into the ease of invincibility. But surely our scars would also pay testament. Maybe the concerted rejection of apathy is enough.